Human history has largely emerged in rural environments, where sprawling savannas and forested river valleys have hosted our ancestors for millions of years.

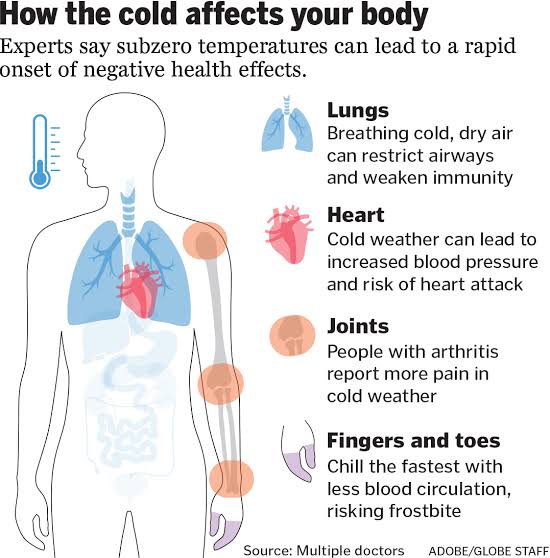

By comparison, cities represent a radically new type of habitat that, despite their many advantages, often stresses our mental health. Research has linked urban environments to an increased risk of anxiety, depression and other mental health problems, including schizophrenia.

Fortunately, research also points to a solution:

Visiting the wilderness, even for a brief period, is linked to a host of mental and physical health benefits, including lower blood pressure, reduced anxiety and depression, improved mood, better focus, better sleep, improved memory, and better healing. faster.

Numerous studies have supported this association, but we still have a lot to learn.

Could just a walk in the woods spark all these beneficial changes in the brain? And if so, how?

A good place to look for clues is: the amygdala, a small structure in the center of the brain involved in stress processing, emotional learning, and the fight-or-flight response.

Research suggests that the amygdala is less active during stress in rural versus urban dwellers, but this does not necessarily mean that rural life is causing this effect. It may be the other way around, and people with this trait are more likely to live normally in the countryside.

To answer this question, researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Human Development devised a new study, this time with the help of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

Using 63 healthy adult volunteers, the researchers asked participants to fill out questionnaires, perform a working memory task, and undergo fMRI scans while answering questions, some of which are designed to induce social stress. Participants were told that the study involved an MRI and walking, but they did not know the purpose of the research.

The subjects were then randomly assigned to walk for one hour in either an urban area (a busy shopping district in Berlin) or a natural environment (the 3,000-hectare Grunwald Forest in Berlin).

The researchers asked them to walk a specific route at either location, without deviating from the track or using their mobile phones along the way. After they walked, each participant took another fMRI scan, with an additional stress-inducing task, and filled out another questionnaire.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) showed a decrease in activity in the amygdala after a walk in the woods, the researchers reported, supporting the idea that nature can lead to beneficial effects in areas of the brain associated with stress.

“The findings support a previously assumed positive relationship between nature and brain health, but this is the first study to demonstrate a causal link,” says environmental neuroscientist Simon Kohn, head of the Lise Meitner Group for Environmental Neurosciences at the Max Planck Institute for Humans.

Participants who toured the forest also reported regaining more attention and enjoying the same walk than those who walked in urban areas, a finding consistent with the results of the fMRI study as well as previous research.

The researchers also learned something interesting about the people who walked in urban areas.

Although amygdala activity did not decrease as much as those who walked in nature, it did not increase either, after spending an hour in a crowded urban environment.

“This argues strongly in favor of nature’s effects as opposed to urban exposure which causes additional stress,” the researchers wrote. This does not mean that urban exposure cannot cause stress, of course, but it may be a positive sign for city dwellers.

The new study provides some of the clearest evidence yet that stress-related brain activity can be reduced by taking a walk through a nearby forest, just as our ancestors did.